LP 19/2021 Drug Smuggling on Bulk Carriers out of Brazil on the Rise

The significant profits in drug dealing and delay in law enforcement have pushed smugglers to risk danger in desperation. In recent years with increasing frequency, bulk carriers and container ships are exposed to losses including detentions, fines and even criminal charges on the crew when drugs are found (hidden in cargo holds/containers or attached to the hull) on board.

According to the Proinde Circular on increasing drug smuggling activity in Brazil, it is important Members take an appropriate level of precautions to prevent potential losses and negative influences on the reputation of ships and seafarers. The circular is attached below along with advice of the Association for Members’ reference.

I. World drug problem

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that global consumption of illicit drugs has increased by more than 30% in the past decade, with about 18 million regular cocaine users worldwide. The prevalence of cocaine use is high in North America (mainly in the United States), Western and Central Europe (Spain, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom), and Oceania (especially in Australia). Notable rises in the use of the narcotic have been registered in Asia and Africa.

In response to the increased demand, there has been extensive growth in coca cultivation and cocaine manufacture in South America. Although potentially stabilised, cocaine productivity rates remain at the highest levels ever recorded due to the greater efficiency of refining laboratories and optimisation of manufacturing and distribution processes. Colombia remains the world’s largest cocaine manufacturer and supplier, followed by Bolivia and Peru.

Although it is not a significant producer of the stimulant drug, Brazil shares extensive unguarded land borders with the three producing countries and is the second-largest cocaine consumer, only second to the United States. While the producers themselves supply most of the North American and Asian markets, Brazil’s many ports in the Amazon and the East Coast and its extensive airport network play a significant role as a transhipment point to ship cocaine between the three Andean countries and established markets in Europe and, more and more, in Africa and Asia.

Brazil is only behind Colombia in quantities of seized cocaine, denoting the country’s importance as a key distributor for the global market. Information released by the Brazilian Federal Police, Customs authorities and media sources indicate a substantial increase in the number of occurrences and the amounts of cocaine interdicted in port facilities and aboard vessels. In some of the incidents, the drug was not discovered until the ship arrived at its destination.

The worldwide expansion in cocaine supply and demand is a hazard to public health and a challenge to law enforcement efforts. It is also a significant threat to international maritime trade, the safe operation of vessels, and the safety of seafarers, who may have to face criminal prosecution in foreign jurisdictions, some of which punish drug offences with the death penalty.

II. Maritime trafficking routes

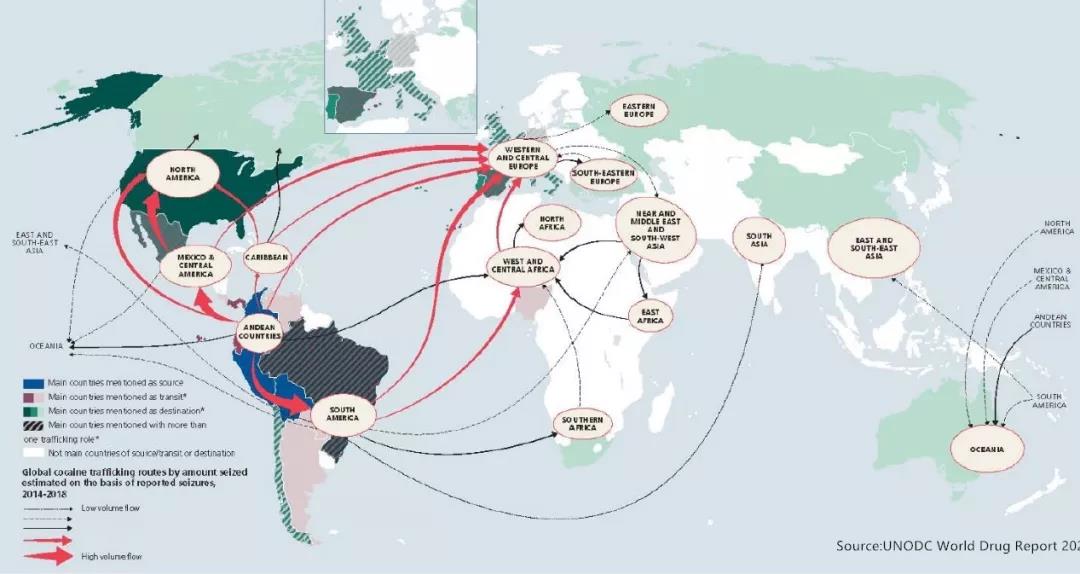

Global cocaine trafficking by amount seized 2014-2018

According to the UNODC, the main flow of cocaine trafficking in the Americas is from Colombia to the United States, via the Pacific Ocean or Panama Canal, or by land, through Central America, and then Mexico, where the drug is smuggled into the USA across the southwestern border.

The second busiest trafficking flow is from the producing countries, mainly Colombia, straight to Europe. Over the years, Brazil has gained relevance in maritime cocaine trafficking to that continent, either directly or through transit subregions, such as West, Central and Southern Africa.

Although most of the drug to Asian markets is dispatched by drug carriers on commercial flights, the cocaine that arrives in China is smuggled chiefly by sea, originating in Colombia, through the transpacific route, and in Brazil via the Cape of Good Hope.

Given the high profitability of cocaine trafficking, globalised organised crime groups rely on the internet and information technology, sometimes gaining corrupt access to digitalised logistics planning and automated systems, to devise methods to exploit the vulnerabilities of commercial shipping routes and move massive quantities of drugs to all corners of the world.

III. Drugs in containers

Packages of cocaine found in the refrigeration compartment

The latest figures disclosed by the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) indicate that over 811 million TEUs are handled in container ports worldwide each year, with less than 2% of containers being screened. It is no wonder that moving large quantities of drugs in containerships remains by far the preferred smuggling method for organised crime groups.

The most common modus operandi for smuggling drugs in containers out of Brazil is the “rip-on/rip-off” method, whereby the cocaine is loaded into the cargo unit at the port of departure and is recovered at the port of destination without the knowledge or cooperation of the shipper, consignee and carrier. It requires corruption of hauliers or port workers at both ends and involves tampering with the original seal, which is usually replaced or repaired to disguise obvious violation.

Drugs are often hidden or incorporated into legitimate cargo shipments, typically involving the cargo owner, packers or port workers. They may also be concealed in the structure of dry containers, such as corner posts, rails, floorings, and into cooling compartments and insulation of walls and doors of refrigerated (“reefer”) containers.

Santos, Latin America’s busiest port, is an important departure point for cocaine shipments. The number of seizures has noticeably increased in recent years, reflecting the growth in maritime cocaine trafficking and, possibly, the result of adoption, by the federal authorities, of objective profiling and risk assessment criteria and non-intrusive screenings with container scanners and sniffer dogs.

Publicly reported seizures of drugs inside containers in Santos alone rose from about 1,672 kilos in 2013 to a record 27 tonnes in 2019. In the same period, the total seizures in the country went from 2,183 Kg to 57 tonnes. Until the first week of April this year, at least ten cases of containerised smuggling were recorded in Santos, with about 4,250 kg of cocaine seized.

Other hotspots for cocaine trafficking in containers are the southern ports of Itajai/Navegantes, Rio Grande, São Francisco do Sul and Paranaguá. The latter is Brazil’s second-busiest container port and, by the first week of April 2021, it recorded eight incidents resulting in over 1,211 Kg of cocaine intercepted.

In Northern Brazil, cocaine smuggled across the extensive triple border with Colombia and Peru is shipped from Manaus to other ports down the Amazon River and in the Northeast region, particularly in the container terminals of Vila do Conde (Barcarena), Pecem, Suape and Salvador.

IV. Drugs on vessels

While drug shipments from Brazil are moved more and more in containers, there is a noticeable rise in the number of cases involving bulk carriers sailing from grain ports with cocaine buried in the bulk cargo, hidden in void spaces or secured to the vessel’s hull.

Drugs can be introduced into all types of merchant ships in a variety of ways. The ingenuity of criminals should never be underestimated.

Items can be brought aboard vessels by stevedores, officials, and contractors, sometimes with the complicity of crewmembers, and hidden in seldom-used compartments or anywhere of difficult access. When the ship arrives at its destination, a port worker associated with the smugglers, or a crewmember, carries the drugs down the gangway ladder or drop them off in the sea in a specific coordinate for them to be retrieved by small waiting boats.

Smugglers also conceal larger amounts of illegal substances with or within any cargo (breakbulk, solid bulks, vehicles), provisions, spare parts, and in any compartment on the vessel’s deck, cargo holds, tanks, machinery space and crew quarters for subsequent collection ashore, with the necessary assistance of corrupt port workers or officials.

Unlike drugs smuggled inside containers that have neither been packed nor sealed by the carrier, drugs discovered inside the vessel tend to shift the risk of detection – and the resulting criminal liability – to innocent third parties, usually the crew. Drug cases invariably cause significant disruptions to the vessel’s operation, even if there is no evidence that the attempted smuggling had the connivance or knowledge of the master, officers and crew.

In a daring developing trend in South American ports, well-trained covert divers reach the bottom of the vessel to attach waterproof packages full of cocaine to the hull surface below the waterline or structures such as sea chest, propeller bracket, rudder space and thruster fittings. Associate divers retrieve the illegal items at the port of destination. This method can take place at anchorage areas or alongside a berth during cargo operations.

Cocaine found by Customs sniffer dogs

V. Liabilities

While possession and cultivation of drugs for personal use in Brazil has been decriminalised, public consumption is punishable with warnings on drug effects, community services for up to 10 months and attendance to educational courses and programs. The penalty for those convicted of drug trafficking ranges from 5 to 15 years in prison, plus a fine and attendance to resocialisation programs. Foreigner offenders, including legal residents and visiting seafarers, may be deported on short notice.

Vessels transporting drugs in Brazil may be detained and searched during criminal investigations by competent authorities. Shipmasters retain overall responsibility for the vessel’s security and crew’s safety. They and their officers and crews may be questioned as witnesses, indicted or taken into custody, with the right to legal assistance. Cargoes, vehicles and containers involved in drug smuggling may be seized as material evidence, confiscated and forfeited.

The apportionment of liability between shipowners and the charterers of a vessel carrying illicit substances is typically resolved through an express contractual provision in the form of clear “anti-drug” clauses inserted in the charter party. The off-hire clauses in the C/P determine the period of delay that generally occurs following the discovery of drugs.

The absence of explicit contractual provisions can give rise to complex disputes; however, the owner usually accepts liability for the losses and costs arising when the master, officers or crew are accomplices or when drugs are found in their possession or belongings. On the other hand, if the drugs were loaded with cargo or containers, liability tends to rest with the charterer.

C/P provisions for drugs found outside the vessel, as on the hull below the waterline, are uncommon as this modality of smuggling is somewhat recent. The tendency is that charterers assume liability because they directed the vessel to the port where the illegal substance was planted. Furthermore, they are contractually responsible for exercising utmost care and due diligence to prevent unmanifested narcotic drugs from being loaded or secreted on the vessel.

VI. Preventive measures

Brazilian ports typically operate under Security Level 1 of the ISPS Code, which requires minimum protective security measures. Nevertheless, the master and crew should consider all national ports areas of potential high risk of contamination with illicit drugs to be on the safe side.

The Association strongly recommends that Ship Security Plan to be performed and crew training to be carried out on board ships trading in Brazil, and there are many precautions that masters, officers and crews can take to increase the level of shipboard security, including:

1. Learn and identify, ideally from the Port Facility Security Officer (PFSO), the level of security in place, CCTV coverage available, local risks and communication channels;

2. Illuminate the deck area, access points and overside of the vessel while in port or at anchor during hours of darkness;

3. Secure and lock areas such as accommodations and deck stores and strictly monitor the activities of stevedores, contractors and other visitors;

4. Maintain the shoreside gangway ladder well-guarded at all times and the seaside ladder stowed and secured in place and conduct regular patrols on deck and access areas;

5. Keep a log of personnel visiting the vessel (including stevedores and other port workers) and ensure that visitors wear adequate PPE;

6. Conduct bag checks at entry and exit at random and whenever there is suspicion about the items carried by visitors and port workers;

7. Search breakbulk volumes and the interior of vehicles and empty containers;

8. Check the integrity of seals and the structure of full containers;

9. Keep a lookout on the working hold not only to ensure that the cargo is in apparent condition but to ensure that no objects are loaded with the cargo or thrown into the hold;

10. Keep stevedores and other shore personnel away from crew quarters and non-working cargo holds, which should remain closed;

11. Log the activities of service barges moored alongside the vessel;

12. Monitor small crafts and workboats lying in the vicinities and look for bubbles of divers. Illuminate suspicious crafts and underwater activities with floodlights;

13. Take photos of the top of the stow of bulk cargo immediately after loading and before closing the holds to record that no objects have been placed on the cargo spaces;

14. Arrange sealing of the cargo holds by independent surveyor upon completion of loading of solid bulks. Arrange unsealing of cargo holds by independent survey at destination;

15. Carry out a full search on the vessel and cargo to look for suspicious packages and bags before leaving a port or shifting to another berth in the same por. Arrange an underwater inspection if there is suspicion or information that drugs may have been sneaked into the vessel’s bottom. Invite the PFSO and the charterer to participate in the exercise.

Proinde advises also that there are few security companies accredited by the Federal Police, Maritime Authority and local Port Authority. Expert ship security and search services are available only in most developed ports. Furthermore, such a novel initiative could lead to misinterpretations by the competent authorities about the good intention of the vessel’s interests in contracting these services. Therefore, at this stage, we will have to rely on the Federal Police and Customs Authorities to perform function of the State and combat illicit drug trafficking.