LP 09/2021 ICS Tanker Safety Guide Fifth Edition Revisions

It has been an industry-wide consensus that over 80% of maritime incidents arise from human errors. Operations on chemical tankers are known to be complicated and require extensive expertise, but the established IMO regulations cannot fully fulfill safe operation and anti-pollution purposes. The ICS Tanker Safety Guide (Chemicals), as supplementary to MARPOL Annex II and other regulations, has provided those working for chemical tankers with a recognized best practice from technical perspective.

The fifth edition was published in January 2021 as a consolidation of experience and a response to user feedback to include revised content and primarily updates on key safety issues. The Association has gone through the latest edition and listed the important information below for Members’ reference.

Major revisions:

- Extended key safety issues to include content regarding entry into enclosed spaces, risk assessments and PPE.

- Revised comprehensively the ship/shore safety checklist to guide seafarers and terminal personnel through important safety checks.

- Adjust the ship/shore safety checklist to be consistent with the International Safety Guide for Oil Tankers and Terminals (ISGOTT) sixth edition.

I. Entry into Enclosed Spaces (Chapter 9)

Although great importance has been attached to safety in enclosed spaces and measures were taken to prevent such incidents, casualties continue to increase as a result of human negligence or impulsive rescue attempts. The latest edition again highlighted the importance of effectively marking enclosed spaces and monitoring atmosphere of deck areas.

9.2 It is recommended that all spaces with hazardous or potentially hazardous atmospheres are systematically identified and marked. On board training and drills should be used to develop routine familiarity with the correct behaviors and procedures associated with enclosed space entry.

Safety awareness on the dangers of enclosed spaces has been strengthened with drills and training sessions carried out frequently. The number of incidents has been reduced in clearly marked areas and 90% of these incidents take place in cargo tanks – accessible but can be easily overlooked. Therefore, entry of cargo tanks should be marked, tagged or locked to prohibit any accidental entry.

9.2.1 Throughout this guide the percentage of oxygen in air is referred to as 21%. However, due to atmosphere characteristics and variation, the percentage of oxygen in air falls several hundredths of a percent below this figure, variously quoted as being between 20.80% and 20.95%. Modern instrumentation with digital indicators can measure so accurately that the full 21% may be impossible to obtain. If an instrument capable of such accuracy is in use, the manufacturer's instructions should be carefully read and understood so that the readings can be properly interpreted.

The fourth edition provided that the oxygen content should be no less than 21%, which can be confusing as the normal level is 20.9%, and in practice some crew members did modified the test result to a value above 21%. Chapter 9.2.1 added the above paragraph to explain oxygen content in air and a note was attached in the sample enclosed space entry permit next to the oxygen readings that national requirements may determine the safe atmosphere range. According to Chinese GB Standard 8958-2006 Safety Regulation for Working under Hazardous Condition of the Oxygen Deficiency, the minimum level of oxygen concentration at working spaces is 19.5% and the threshold of oxygen enrichment was introduced in GB30871-2014 at 23.5% (other standards for reference include 19.5-23.5% CFR, 19.5%-22% GBZ and 20.6-22% CCS). An appropriate range shall be determined by companies before entry is permitted.

9.5.1 Testing for entry in shipyards: During a repair or construction period the ship and personnel on board may be exposed to unexpected and unfamiliar risks and hazards. When at a shipyard, the safety of the ship and its personnel are not entirely under the Master’s control. Responsibility for safety is shared and to an extent depends on the shipyard’s own SMS. All company SMS procedures for enclosed space entry should continue to be followed. It will also be necessary to work in conjunction with the shipyard’s own safety system while not relaxing the ship’s enclosed space entry standard.

9.6 Protections and controls that can reduce the risk:

- The most effective way to eliminate the risk is not to enter an enclosed space.

- Companies and Masters should ensure that personnel enter enclosed spaces only when there is no practicable alternative.

- Where there is no alternative, the company should ensure that procedures for safe entry are in place.

- Masters should verify that procedures for entering enclosed spaces are fit for purpose, robustly implemented and followed, and that every entry is planned in line with these procedures, no matter how often they happen.

9.10 Atmosphere monitoring of deck areas

Many of recent enclosed spaces incidents take place in areas that do not seem to be so enclosed as some chemical vapors are heavier than air and tend to flow along the deck and accumulate in low spots. Chemical tankers have complicated deck structures and this, together with the comprehensive pipe work and other equipment fitted, provides numerous areas where harmful vapors can accumulate. It is recommended in the fifth edition that atmosphere samples should be taken at deck areas and areas known to be more at risk from hazardous vapors should be known to the crew.

Note: over half of the deaths in enclosed spaces occurred from impulsive or ill-prepared rescue attempts.

II. Risk Assessments (Chapter 3.7)

Risk assessments are a fundamental part of the SMS. Resolution MSC.271(85) Amendments to the ISM Code provided in section 1.2.2 that the company should “assess all identified risks to its ships, personnel and the environment and establish appropriate safeguards”. There is no industry standard or minimum criteria for a risk assessment, but the purpose is to meet the needs of the company and to help shipboard personnel to plan and carry out work safely. Companies should establish a set of procedures that fits their organizational structure and fleet characteristics. This chapter of the Guide was revised to address the problem where risk assessments are reduced to paperwork in practice and guidance on the timing and process of evaluation of the risks are provided in detail.

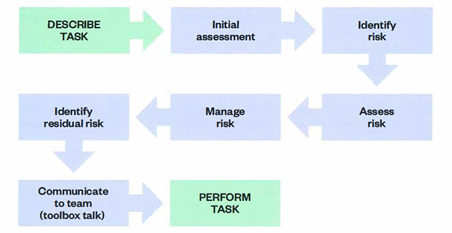

The above is a basic risk assessment process, and companies may use different terminology or include other stages in the process. To instruct seafarers on the tasks to be carried out, companies may need specific requirements on the following matters.

- Companies may provide a set of generic risk assessments for a wide range of tasks and activities that are carried out on board ships. However, these assessments may not always reflect the specific circumstances of the operation and the impact of such circumstances on the assessed risks, such as changes in weather conditions, ship motion and daytime of nighttime operations. The company should provide guidance in the SMS on how and when to use generic risk assessments. If the assessment carried out on board presents a level of risks that agrees with the company result, then the existing control measures should be followed but if a higher level of risks is presented, then additional control measures should be considered. If high risk activities are identified in the process, another round of risk assessment should be carried out pursuant to company requirements.

- The relationship between checklists, permits to work and risk assessments should be clearly described so that the shipboard personnel understand when the risks can be contained simply with checklists or work permits, and when checklists and work permits can be used effectively to support risk assessments.

- A risk assessment procedure should be developed for non-routine operations, meaning operations that are not covered by standard company procedures and therefore the risks involved in carrying out the task have not been comprehensively assessed and addressed. Although some aspects of the operation may be covered by existing procedures, it is important that a detailed risk assessment is carried out prior to a non-routine operation to address all identifiable risks and to plan accordingly. In most cases, a non-routine operation requires approval from shore management. Some examples of non-routine operations were introduced:

- entry into an enclosed space where the atmosphere is known to be unsafe;

- decision to continue operation before a defective alarm/equipment is repaired;

- use of an emergency cargo pump;

- decision to continue operation when a third party tank cleaning advice does not comply with company procedures;

- exceptional circumstances where the ship is not able to comply with the P&A Manual;

- use of special cleaning agents that may create additional hazards for the crew when a written procedure does not exist;

- process to recirculate a flammable product for cleaning of a non-inerted cargo tank;

- process to clean non-cargo spaces into which cargo or vapors have leaked.

- A report system of incidents, near misses and accidents should be established to encourage crew members to provide information for companies to analyze the root causes and determine corrective actions.

III. Personal Protective Equipment (Chapter 3.11)

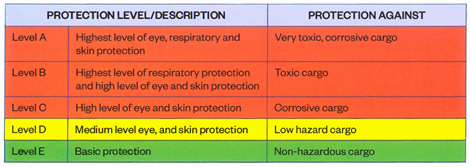

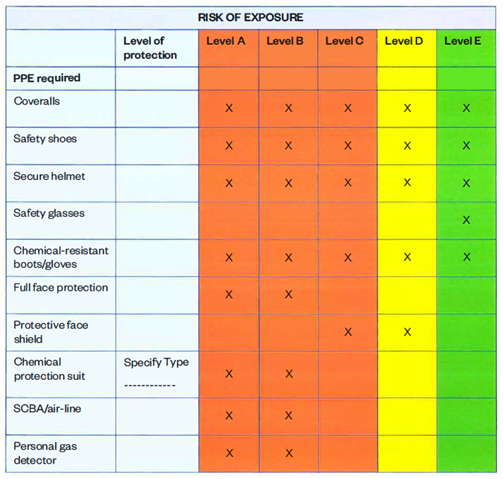

PPE protects the wearer from exposure to hazardous working conditions by providing a barrier between the wearer and a hazardous environment. The effectiveness of the barrier will be lost if the PPE is incorrectly used, and this is especially important on chemical tankers. Companies are recommended to thoroughly assess the risks involved and identify cargo-specific PPE for all products on board ships to ensure consistency across their fleets and all crew members are adequately protected. Also, it is encouraged to put up a poster identifying different levels/types of protection as a direct reference.

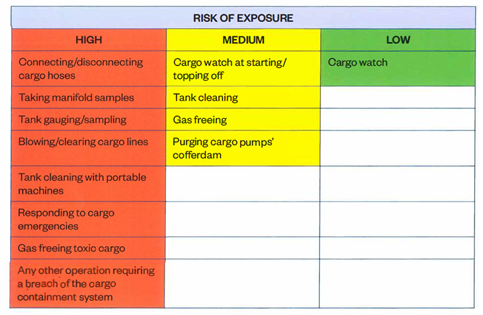

A PPE matrix is provided in the appendix of the Guide with examples of different levels of risks. Individual company SMS should identify the risk level and PPE requirements for ships under their control.

PPE Matrix Figure 1 Activities and risk

Figure 2 Level of protection matrix

IV. Ship/Shore Safety Checklist (Appendix B)

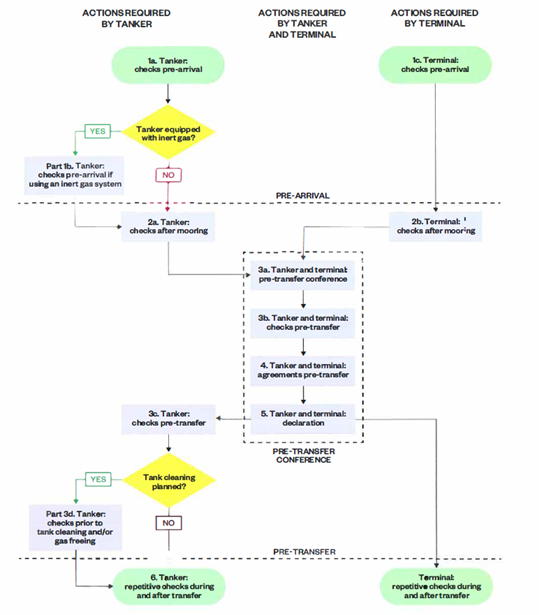

The fifth edition revised the ship/shore safety checklist to include 4 parts – pre-arrival, checks after mooring, checks pre-transfer and summary of repetitive checks during and after transfer. The 1a, 1b, 1c, 2a, 2b, 3a and 3b in this guidance have common reference numbering with those in ISGOTT. For checklists 3c and 3d with different numbering from the equivalent ISGOTT checklists, both are included for ease of reference. Each question provides a primary reference where additional guidance on the subject may be found in the Guide. All the questions should be answered with the “yes” box checked, except in Part 4, and if a “yes” answer is not possible, an appropriate comment should be written in the “remarks” column. If the answer is not confirmed, it may be appropriate to delay or cancel the transfer operation.

B.3 Actions required by tanker and terminal

V. Conclusion

Apart from above revisions, the Guide was adjusted to include some other content for easier reference by shipowners and seafarers. It is recommended that Members and seafarers carefully read the Guide, understand whether the operations on board ships and procedures are compliant as required by company SMS or by conventions and regulations, and hopefully to execute best practice of operation for safety and anti-pollution purposes.

For more information, please contact Managers of the Association.